Folkworks Book Review of Woody Guthrie L.A.

Folkworks Book Review of Woody Guthrie L.A.: 1937 to 1941

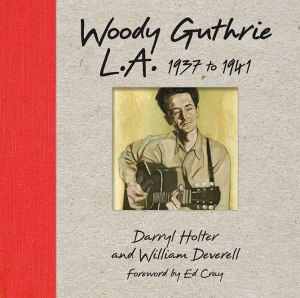

Woody Guthrie L.A.: 1937 to 1941

Darryl Holter and William Deverell

$40.00 / 50+ vintage photos

208 pages / hardcover / 9″x9″

Preorder this book at http://www.angelcitypress.com/products/guth

Folkworks Book Review of Woody Guthrie L.A.: 1937 to 1941

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

By Ross Altman, PhD

Original Article Here at http://folkworks.org/reviews/folkworks-book-reviews/46002-woody-guthrie-l-a-1937-1941

This account of Woody Guthrie’s pivotal four years in Los Angeles from 1937 to 1941—during which he became the political songwriter who influenced four generations of American folk singers—from Bob Dylan to Bruce Springsteen—will send a seismic shockwave through the standard narrative of the folk revival of the1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s. Measured on the Richter Scale, I would put it at a 6.7—in the same territory as the 1994 Northridge earthquake. That narrative—told many times over in books and movies—centers the folk revival in New York City, most particularly in Greenwich Village, where clubs like Gerdes Folk City, the Bottom Line, the Bitter End and the Village Vanguard played host to a Russian novel’s cast of characters—from the Almanac Singers, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, the Weavers and Pete Seeger to “Woody’s Children,” Odetta, Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton, Dave Van Ronk, Fred Neil, the Greenbrier Boys, the New Lost City Ramblers, Len Chandler, Buffy Sainte Marie, Peter, Paul and Mary and eventually—after she left Cambridge—Joan Baez.

This is the “Big Bang” of the Folk Revival and Holter and Deverell have traced it back to its source—like Darwin on the Galapagos Islands looking for the Origin of Species, or Stephen Hawking looking into a Black Hole for the secret of the universe.

It began with a radio program—on KFVD in Los Angeles—called “Woody and Lefty Lou.” “Lefty Lou” was Maxine Crissman, like Woody a Dust Bowl refugee, but from Missouri. Woody named her “Lefty Lou” because she was left-handed and it rhymed with “Ole Mizzou.” By the time he moved back east four years later he was known up and down the state—in Steinbeck’s words—“Woody is just Woody—a lot of folks think he has no other name.”

It was Los Angeles where he wrote Union Maid, after a union meeting where a female member came up to him after the show and said, “Woody, your songs talk about ‘the brothers’ this, and ‘the brothers’ that—aren’t there any songs about union women?” So Woody promptly went home and wrote one, based on a popular ballad from 1910—Redwing—which began “There once was an Indian maid…” which Woody changed to “Union maid.” He built on Joe Hill’s one-man revolution in songwriting, taking both hymns and popular tunes and rewriting them with words that working people could take as their own and—in Woody’s words—“fix what was wrong.”

If a hymn said, “You got to walk that lonesome valley by yourself,” Woody changed it to “You got to go down and join the union for yourself;” if a hymn said “I can’t feel at home in this world anymore,” looking happily toward Heaven in the world to come, Woody changed it to reflect the desperation of the Dust Bowl refugees he was singing for on the radio, “I ain’t got no home in this world anymore.” His clear-eyed observation “the gambling man is rich and the working man is poor, and I ain’t got no home in this world anymore” wasn’t a promise of a better afterlife, it was a warning about this life and what to do about it.

Woody blazed the trail that twenty-five years later “Woody’s Children” would follow—Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton, Malvina Reynolds, Len Chandler and many others—using folk music as an on-going commentary on the times they lived in, using both humor and bitter protest to highlight injustice and inequality. Woody created the roadmap that future folk singers would travel, as they sang both his songs and new songs of their own. That was the genesis of the folk revival, and as Darryl Holter and William Deverell recount, it began not in some Greenwich Village coffeehouse, but the streets and union halls and one visionary radio station in Los Angeles that gave Woody a voice.

And in a real sense, it began “on the nickel,” Skid Row on 5th Street in downtown L.A. That’s where Woody would carry his guitar on his back into a bar or restaurant and set up shop asking for requests and passing the hat for tips. Between them Woody and Lefty Lou knew hundreds of traditional songs from the Midwest, but on the radio for a half hour show five days a week they eventually ran out of fresh material and Woody realized he would have to start creating his own songs—based on the sources he knew so well. One of his first new songs in this vein was about the Los Angeles New Year’s Flood of 1932. He hadn’t experienced it himself, but a lot of his audience had, and disaster songs were a staple in folk and country music. Woody had already lived through the worst natural disaster of his lifetime—the dust storms of Oklahoma, and had a lot of stories to tell. One of his best-known Dust Bowl Ballads was born right here in L.A., Do Re Mi:

Lots of folks back East they say, is leavin’ home most every day

Beatin’ their hot old dusty way to the California line

‘Cross the desert sands they roll, getting’ out of that old dust bowl

Think they’re goin’ to a sugar bowl, but here is what they find:

Now, the police at the port of entry say,

“You’re number fourteen thousand for today.”

If you ain’t got the do, re, mi, friend, you ain’t got the do re mi

Why you better go back to beautiful Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Georgia, Tennessee.

California is a Garden of Eden, a paradise to live in or see;

But believe it or not, you won’t find it so hot

If you ain’t got the do re mi.

(Do Re Mi, Words and Music by Woody Guthrie;

© Copyright 1961 (renewed) by Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc. & TRO-Ludlow Music, Inc. (BMI))

What makes this book such a delight and a revelation to read through, though, are not the excavations of Woody’s classic songs and pinpointing their composition to Los Angeles, but the countless unknown songs about his everyday experiences tossed off from day to day—such as Downtown Traffic Blues, about an accident he and Lefty Lou got into while driving to work at their radio show:

A driving your car by night or day

In the downtown traffic of old L.A.

It’s piece by piece they’ll take it from you

And leave you settin’ on top of the frame.

Hey! Hey! Mister! Hold yo’ hand

Somebody will knock you to the Promised Land;

When you git to Heaven, won’t be no Drivin’

There’ll be no Downtown Traffic Blues.

And his cautionary tale about the dangers lurking around every corner for fellow migrant families on Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles is captured in Skid Row Serenade:

If you go down on old Fifth Street

Keep your money in your jeans

‘Cause the peaches down on 5th St.

They ain’t got a bit of cream.

You can go down on old 5th St

Where the people hit it hard—

But if you’ve got a little money

It’s the Wilshire Boulevard.

Examples of Woody’s throwaway songs abound in this book, and they reveal the truth of Chekov’s long-ago counsel to young writers on “how to write a good short story;” “Write a thousand,” said Chekov—and that’s exactly what Woody did. Eventually time sorted them out and kept songs like “Pastures of Plenty” and “This Land Is Your Land.” But without Woody’s day-to-day setting of pen to paper there would have been no classics. That is one of the great unheralded lessons of Woody Guthrie L.A. 1937 to 1941. It presents Woody in all his naked glory, writing as far as we know something like a song a day, many of them sung only once on the radio and documented only in the “Air Check” recordings that Darryl Holter faithfully documents in the extensive discography. This is a masterpiece of historical scholarship on a subject many readers will mistakenly assume they already know. Be assured, this is a Woody Guthrie you haven’t met before—the making of an artist who eventually became the iconic figure we now know.

The irony is that the publisher—Angel City Press—that brought this transformative book to life resides on the very boulevard—Wilshire Blvd in Santa Monica—that Woody satirizes in his Skid Row Serenade—the unlikely source of Holter and Deverell’s love letter to Skid Row—for having given birth to America’s greatest folk singer. That’s a fine example if you ask me of what Marx called the contradictions of capitalism. At the book-signing publication party I attended back in December it cost me $18 to park in the nearest public parking lot (though in fairness there was apparently free parking in the building that hosted the party—I just couldn’t find it). The building itself—which had a bar and restaurant where the authors and publishers held forth—was best known for the oil company emblazoned on the front (I don’t recall which one). This was—all the way around—Big Money being temporarily commandeered by People’s Art. Woody could not have afforded to attend his own book signing. Nor could he have afforded the book, with a price tag of $40.

You may recall Woody’s reason for writing The Ballad of Tom Joad, which he wrote in 1940 after seeing John Ford’s film version of John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath three times in a row. He said he wrote it for the folks back in Oklahoma who “didn’t have a dollar to buy the book—or even a quarter to see the movie.” He figured that his song would get back to them for free so they could find out “what Preacher Casy said:”

Ever’body might be just one big soul,

Well it looks that-a-way to me

So wherever you look, in the day or night,

That’s where I’m a gonna be, Ma,

That’s where I’m a-gonna be.

Wherever little children are hungry and cry

Wherever people ain’t free

Wherever men are fightin’ for their rights

That’s where I’m a-gonna be, Ma

That’s where I’m a-gonna be.

(Tom Joad, Words and Music by Woody Guthrie

© Copyright 1960 (renewed) and 1963 (renewed) by Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc. & TRO-Ludlow Music, Inc. (BMI)

And that’s why we should care about Darryl Holter and William Deverell’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man—because he became the artist who wrote those timeless words. Thank you to Holter and Deverell for making that portrait available to all who care about the genesis of this great American artist. Woody Guthrie’s brief four years in Los Angeles became the seedbed out of which American music became something larger and more meaningful than ever before. It’s the reason why another great American artist twenty years later would be inspired to write

Hey, hey, Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song

‘Bout a funny ol’ world that’s a-comin’ a long

Seems sick an’ it’s hungry, it’s tired an’ it’s torn

It looks like it’s a-dyin’ an’ it’s hardly been born.

(Song to Woody by Bob Dylan

Copyright © 1962, 1965 by Duchess Music Corporation; renewed 1990, 1993 by MCA)

Every library should own this book, and that way some young Woody Guthrie wandering around Los Angeles today, without enough money to buy a decent meal, can still take out a library card and read this $40 book about hard times and the man who would later write: “If the fight gets hot, the songs get hotter.” (Woody Guthrie)

Or do what Abbie Hoffman advised: “Steal This Book!”

Buy it, borrow it, or steal it, but by all means read it!

Woody Guthrie L.A.: 1937 to 1941

Darryl Holter and William Deverell

$40.00 / 50+ vintage photos

208 pages / hardcover / 9″x9″

Preorder this book at http://www.angelcitypress.com/products/guth

Follow Darryl Holter Music

Recent Posts

Darryl Holter

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur. Darryl Holter is also a historian who has written on Woody Guthrie and a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.