Darryl Holter Tangled Up in Dylan

Folkworks Review

Darryl Holter Tangled Up in Dylan

at the Caña Rum Bar – February 19, 2016

By Ross Altman, PhD

Dateline, Los Angeles~ The hottest ticket in town turned out to be in a hidden rum bar in the unknown Petroleum Building in the 700 block of Olympic Blvd downtown tonight, just a block away from the Grammy Museum. An SRO crowd (I know, because I was standing throughout) saw local folkie historian Darryl Holter—co-author of the new book Woody Guthrie LA 1937-1941 (see my review)—in a show he called Holter Does Dylan. It was also it turns out a birthday present to himself, for when I got there I saw a beautiful birthday cake in front of the stage, and Darryl was tuning up in front of the microphone.

I first met and heard Darryl twenty years ago, while performing at a labor conference at UCLA, where he was a part of the Institute for Labor Studies (which grew out of Art Carstens Institute for Industrial Relations). Professor Carstens was the father of a great woman I was friends with, and in love with—the late Betty Carstens—who became Mike Davis’ girlfriend when he organized SDS in Los Angeles—and recruited me to became president of the UCLA chapter in 1965. Carstens’ department was the voice for the labor movement in LA, and Darryl found a home there as a budding labor historian when he moved from Minneapolis, Minnesota where he grew up. That’s where he became acutely aware of Dylan’s music—as a fellow Minnesotan.

Darryl has a great story about meeting Dylan in Osseo, Wisconsin in 1976, where he was traveling with his eight-year old daughter Rachel. She looked into a restaurant window and reported back to her dad, “Daddy, there’s somebody pretending to be Bob Dylan sitting in the restaurant.” Darryl peeked into the window, did a double-take, and said, “Honey, he’s not pretending—that’s Bob Dylan.” He was a small man sitting with two big body guards. His companion said, “Don’t go in there—don’t bother him.” Darryl didn’t’ think twice; he walked in with his daughter and introduced her to the bard. “She knows your songs, Mr. Dylan.” Dylan looked up and asked the girl her name. “Rachel, Sir.” “That’s a pretty name.” “Do you really know my songs, Rachel?” “Oh yes, sir; we listen to them all the time.” “Which ones?” “I can sing Tangled Up in Blue.” That got his attention; he assumed it would be Blowing In the Wind. Dylan smiled as she launched into the haunting ballad from Blood On the Tracks. He could hardly believe an eight-year old would be singing Tangled Up in Blue—which she knew flawlessly. He smiled and thanked them for saying hello. The interview was over—and never to be forgotten.

Darryl is a born teacher, even when he is singing. He prepared a note sheet handout for everyone in the back room of the Caña Rum Bar in the Petroleum Building downtown—which—surprise—Holter owns. That’s how he accommodates all his guests with complimentary parking. I mentioned in my book review that I couldn’t find the building’s parking lot the first time around—where Holter held their book’s publication party last December, and wound up paying $18 (flat rate) to park across the street at the nearest public parking lot. But this time I saw the brightly lit neon sign “Caña Rum Bar” entrance and enjoyed the complimentary parking privileges of the other invited guests.

Knowing what it cost to park in this neighborhood I allowed what killed the cat to get the better of me and asked the lady parking attendant in the basement what it would cost to pay for “complimentary parking” for all of one’s guests at the bar. Before she could tally it up I then wondered aloud, “Does Darryl own the building?” “Yes,” she replied simply, and knocked me off my feet. So here we have the author of the pre-eminent Skid Row Dust Bowl folk singer’s crucial four years in LA that launched the folk revival in the ironic position of a major league property owner in the toniest neighborhood outside of Rodeo Drive. It gets curiouser and curiouser, Alice cried. For what makes this concert special is that—as opposed to every other concert in LA last night—Holter’s was the only one that did less than zero publicity. Every other show in town sent out press releases to local media, emails to various lists, handed out fliers, posted on web sites, and gave away free tickets to paper the house.

Darryl is the only concert promoter I know who deliberately told people that unless you were invited, there was no room at the inn. “By Invitation Only!” the invitations began. Here it is, as mysterious and tantalizing as a Dylan song:

By Invitation Only: Holter Does Dylan

Bob Dylan and Darryl Holter are both Minnesotans. Bob Dylan began performing his songs while he was a student at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis in the early 1960s. Darryl Holter heard Dylan’s songs when he was in high school and quickly learned the early Dylan discography.

Now Darryl revisits his own musical roots with a set of Dylan songs from the 1960s and ’70s that propelled Dylan to his iconic status as the singer-songwriter of the 20th century.

On Friday, February 19th Darryl will perform a solo set of Dylan songs at the Cana Club (Caña Rum Bar), the “hidden” bar located in the Petroleum Building. Cana will provide Happy Hour pricing. The event begins at 5:30pm.

Space is limited and the event is private and by invitation only. If you receive this invitation, then you have been invited.

I felt like Harry Haller in Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf, who receives a strange note telling him where to be. If memory serves me well (you’ll excuse the Dylan riff) that is the first and only time I have heard about a secret concert that only welcomed invited guests. Or maybe it’s just the only time I have been invited to one. I don’t have many friends; writers seldom do—and they often lose the ones they have—by telling the truth—which is probably why Mark Twain advised them to do it—but only as a last resort.

Actually, I have heard about one other such concert: Elton John did one recently for music industry insiders to introduce his upcoming album The LA Times reviewed it, so that puts Darryl (and me as the local press) in the rarified air of Elton John and the Times. There’d be days like this, my mama said; (uh, Van Morrison said that…)

The Dylan song I first heard Darryl perform at that long-ago labor conference is from The Times, They Are a-Changing: The North Country Blues. It’s still in his repertoire and was the second song in the “Holter Does Dylan” set. Dylan rarely performs it live, but it is a masterpiece of labor history, written from the point of view of a woman who has seen her entire family destroyed by the loss of mining jobs that once sustained them:

My children will go

As soon as they grow

For there ain’t nothing here now to hold them.

Darryl does it with real feeling, and it was the conviction he brought to it that got my attention when I first heard it—and inspired my lasting affection for his music that prompted my recent essay on the Woody Guthrie Prize and how I thought he deserved it.

The song grew out of Dylan’s childhood memories growing up on the northern iron range in Hibbing, Minnesota.

Holter opened the show with the song Dylan has lately been closing his shows with—Blowin’ in the Wind. Of the two, I prefer Dylan’s placement, since as his most famous it is a hard song to follow. His handout indicates that it was written “in 10 minutes in a coffee shop in NY in 1962.” That may be overstating it a little. I would say it was written in nine months and 10 minutes. The nine months would account for the time Dylan spent in the New York Public Library, doing research on the Civil War. That’s where he learned about the “cannonballs” that fly—in lieu of the bomb—which everyone else was writing about in 1962. Dylan doesn’t mention the bomb in so many words—but he evokes it by using the image “before they’re forever banned.” Even more to the point, that is where he would have come across the abolitionist song No More Auction Block; which was the source of the tune he adapted for Blowin’ in the Wind. It’s a modern classic all right, but it is grounded in a Civil War anti-slavery classic. That immersion in our genuine history—including musical history—is what raises Dylan’s song heads and shoulders above the many similar protest songs of the early sixties. His song may have been born where he finally set pen to paper in a busy coffee shop for 10 minutes, but the song was conceived in the peaceful confines of a library, far from the madding crowd.

Here is Darryl’s entire set list, including two songs he skipped over:

1) Blowing in the Wind

2) North Country Blues

3) Don’t Think Twice

4) Mr. Tambourine Man

5) It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue (not performed)

6) I Want You

7) Just Like a Woman

8) Lay, Lady Lay (not performed)

9) Tangled Up in Blue

He indicated afterwards that he was having some vocal problems and so left out two songs, but I didn’t notice it. I assumed he left them out because he was reading the audience and thought it was long enough with seven songs. Good performers do that kind of thing all the time.

The most noteworthy song on the list in terms of its impact during the performance was Just Like a Woman. Darryl did a very intimate beautifully subdued version, finger-picked with just his bare fingers, and harmonica, in the key of G. What made it stand out to me were two things. He mentioned during his introduction (also included in his handout) that “the song was controversial with the emerging feminist movement…because of phrases that seemed sexist towards women.” In the context of that footnote I found it especially moving to see a lovely Asian woman beautifully dressed standing next to me in the back silently mouthing all of the words—singing softly to herself—throughout the song. How sexist could it be, I wondered, if a perfect example of its subject would take it so to heart?

Things have changed, I guess. Oh yes, Dylan said that too.

After the show I accompanied Darryl down to the parking lot, put my hand on his elbow and said, “All right, my friend, pay attention.” And there I serenaded him with the Dylan song everyone should hear for their birthday, which is actually today, February 20.

Happy Birthday, Darryl;

Thank you for a beautiful evening;

For the songs, the notes, the non-alcoholic ice water,

the chocolate cake, and the tasty quesadillas.

May you stay Forever Young.

Follow Darryl Holter Music

Recent Posts

Darryl Holter

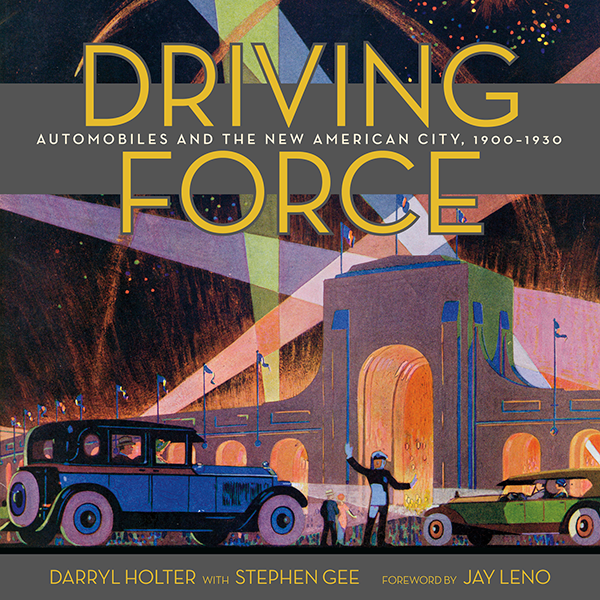

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur. Darryl Holter is also a historian who has written on Woody Guthrie and a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.