Darryl Holter Book Review Woody Guthrie Annual

Darryl Holter Book Review Woody Guthrie Annual

Managing Editor: Will Kaufman, University of Central Lancashire

The Woody Guthrie Annual is an open-access peer-reviewed journal containing the most up-to-date scholarship on Woody Guthrie, his work and his cultural and political significance. The journal is published once a year, between June and December.

In addition to peer-reviewed scholarly articles, The Woody Guthrie Annual contains book and record reviews, news, and notices of relevant events. The journal is comprehensively indexed and archived in the appropriate online repositories. For more information on the life and legacy of Woody Guthrie, please visit www.WoodyGuthrie.org

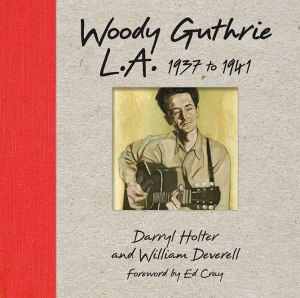

Darryl Holter and William Deverell, eds., Woody Guthrie L.A. 1937 to 1941. Santa Monica: Angel City Press / Hardcover, $40.00.

This collection of twelve essays grows out of the 2012 centennial conference on Guthrie’s Los Angeles years hosted by the University of Southern California. It is an attractive and richly illustrated collection, with many of the images rarely seen before, and with e s s ays by some of the chi e f contemporary Guthrie scholars. As Darryl Holter argues in the opening essay bearing the same title as the book, “The few years Woody spent in Los Angeles were years of rapid professional, musical, and political development” (13). Linking a discussion of Guthrie’s early musical influences in Oklahoma and Texas to the outpouring of his KFVD radio songs from 1937 to 1939, Holter rightly situates Los Angeles as a crucial site of Guthrie’s creative unlocking. It was in Los Angeles where Guthrie first developed a sense of belonging to an oppressed group — “my people” as he famously called them — while at the same time being offered a platform that most of that group had been denied: a radio station with a microphone, a sizeable audience, and a committed New Dealer as the station’s manager. Holter charts Guthrie’s artistic and political growth “from populist to radical” through a mixture of biographical narrative and attention to indicative songs, both popular, such as “Do Re Mi,” and the lesser-known, such as “Fifth St. Blues,” “Downtown Traffic Blues,” “Stay Away from Home Brew,” “California California,” and “A Watchin’ the World Go By.” Clearly the focus in Holter’s introductory essay, as in the collection as a whole, is on the phenomena of Guthrie’s transformation — a concept that crops up repeatedly throughout the book.

Dan Cady and Douglas Flamming offer an insight into the importance of Guthrie’s “rambling” — not only in geographical terms but also in terms of his political and social consciousness. As he rambled to and through California, he also rambled away from some previously entrenched positions, notably his early racism: hence the authors’ choice of a title, “Ramblin’ in Black and White.” Some of the markers along Guthrie’s journey of racial awakening are by now familiar: his retrospective, and largely fictional, fashioning of race-mixing in the boxcars of Bound for Glory; the impact of the 1911 Nelson lynching in Okemah; Guthrie’s racist doggerel in his unpublished “Santa Monica Social Register Examine ‘Er,” and the metaphorical slap in the face he received from an outraged African American audience member following Guthrie’s performance of “Run, Nigger, Run” on his radio show. (And here is an opportunity to correct an historical error perpetuated by a number of Guthrie scholars, including myself. Quite understandably building upon prior published research, Cady and Flamming name the author of that influential letter as Howell Terrence. As I discovered during my last visit to the Woody Guthrie Archives, that letter was in fact written anonymously upon stationery boasting an address, Howell Terrace.) Cady and Flamming situate Guthrie’s racial awakening into a number of further milestones: the composition of the song “Slipknot,” his anti-lynching artwork, and, most significantly, the impact of his friendship with Lead Belly. A particularly delicious find is James Forester’s review, in the Hollywood Tribune of July 3 1939, of Guthrie’s self-published booklet, On a Slow Train Through California (“By Woody, th’ Dustiest of th’ Dustbowl Refugees”). Guthrie typed and mimeographed the copies himself, and as Forester wrote, “Now Woody sells it to his listeners every day over KFVD at 2:15 p.m. when he sings with his ‘geetar.’ He gets two bits for the book …. If Steinbeck ever needs a witness in a court of law to prove that history about the Joads is true, I think he should take Woody” (69). Clearly Forester was one of the earliest and most willing subscribers to the mythic persona that Guthrie so carefully and deliberately constructed during his two-year tenure at KFVD.

Dan Cady and Douglas Flamming offer an insight into the importance of Guthrie’s “rambling” — not only in geographical terms but also in terms of his political and social consciousness. As he rambled to and through California, he also rambled away from some previously entrenched positions, notably his early racism: hence the authors’ choice of a title, “Ramblin’ in Black and White.” Some of the markers along Guthrie’s journey of racial awakening are by now familiar: his retrospective, and largely fictional, fashioning of race-mixing in the boxcars of Bound for Glory; the impact of the 1911 Nelson lynching in Okemah; Guthrie’s racist doggerel in his unpublished “Santa Monica Social Register Examine ‘Er,” and the metaphorical slap in the face he received from an outraged African American audience member following Guthrie’s performance of “Run, Nigger, Run” on his radio show. (And here is an opportunity to correct an historical error perpetuated by a number of Guthrie scholars, including myself. Quite understandably building upon prior published research, Cady and Flamming name the author of that influential letter as Howell Terrence. As I discovered during my last visit to the Woody Guthrie Archives, that letter was in fact written anonymously upon stationery boasting an address, Howell Terrace.) Cady and Flamming situate Guthrie’s racial awakening into a number of further milestones: the composition of the song “Slipknot,” his anti-lynching artwork, and, most significantly, the impact of his friendship with Lead Belly. A particularly delicious find is James Forester’s review, in the Hollywood Tribune of July 3 1939, of Guthrie’s self-published booklet, On a Slow Train Through California (“By Woody, th’ Dustiest of th’ Dustbowl Refugees”). Guthrie typed and mimeographed the copies himself, and as Forester wrote, “Now Woody sells it to his listeners every day over KFVD at 2:15 p.m. when he sings with his ‘geetar.’ He gets two bits for the book …. If Steinbeck ever needs a witness in a court of law to prove that history about the Joads is true, I think he should take Woody” (69). Clearly Forester was one of the earliest and most willing subscribers to the mythic persona that Guthrie so carefully and deliberately constructed during his two-year tenure at KFVD.

Even more revealing and compulsive as an historical detective story is Peter La Chapelle’s essay, “The Guthrie Prestos: What Woody’s Los Angeles Recordings Tell Us About Art and Politics.” La Chapelle is the pioneering historian of Guthrie’s KFVD years; his Proud to Be an Okie: Cultural Politics, Country Music, and Migration to Southern California (2007) remains in the vanguard of California music studies. It was La Chapelle who first unearthed what have been described as Guthrie’s aircheck recordings for KFVD, pressings of “Big City Ways,” “Skid Row (Serenade),” “Do Re Mi,” and “Ain’t Got No Home” on “two lacquer covered aluminum discs, both adorned with bright orange labels emblazoned with the words ‘Presto U.S.A.’” (75). One senses the historian’s exhilaration upon finding these treasures, as La Chapelle recounts his encounter with Harry Hay, veteran gay activist and sometime partner of Will Geer, who gave him the discs (which, as La Chapelle points out, are not exactly air-check recordings, but are more likely demos made by Guthrie on KFVD recording equipment “in an effort to launch a commercial hillbilly career” [83]). In between some sustained textual analysis of Guthrie’s song lyrics, La Chapelle proposes, quite persuasively, that the Presto recordings “suggest that Woody harbored a complicated attitude about the role of commercialization in his music while in Los Angeles”.

Tiffany Colannino’s essay, “Woody’s Los Angeles Editorial Cartoons,” offers a cogent introduction, with an extensive sample of high quality, fullsize, full-color reproductions, of Guthrie’s artwork covering the Los Angeles mayoral elections of 1938. Colannino is the former archivist of the Woody Guthrie Archives, and thus in an authoritative position to declare that these cartoons comprise “Woody’s earliest known series of artwork, a collection that has quite surprisingly survived in pristine condition” — the survival of which indicates “that they were personally important to Woody, and may have acted as his portfolio, showing a variety of examples of editorial cartooning styles”.

Philip Goff’s “In the Shadow of the Steeple I Saw My People” examines the impact of religious culture — the “public performance of religion” (100) — upon Guthrie, from his Pampa days as a faith-healing “trouble buster” (described with embellishment in Bound for Glory) to his immersion into the Los Angeles radio scene. There, he faced particular competition from two popular programs, “part religious and part entertainment”: William B. Hogg’s Little Country Church and Charles E. Fuller’s Old Fashioned Revival Hour, both of which forced Guthrie to up his game in what Goff calls “his intersection with Los Angeles religious radio from 1937 to 1939”.

The late Ed Robbin’s “Woody and Will” is the second of the collection’s reprinting from a previously published source. Extracted from Robbin’s memoir, Woody Guthrie and Me (1979), the chapter is a first-hand account of Robbin’s role in introducing Guthrie to arguably his most influential friend and mentor in Los Angeles, Will Geer. Readers of Robbin’s memoir will recall in particular the transcript of Robbin’s final conversation with Geer, a sustained reflection on their mutual friendship with Guthrie, which is included in this reprinting.

Ronald Briley offers “Woody Sez: The People’s Daily World and Indigenous Radicalism,” devoted to a close reading of selected “Woody Sez” columns appearing in the People’s Daily World between May 1939 and January 1940. Briley examines Guthrie’s rhetorical strategies in engaging with (among a variety of topics) living standards, Wall Street speculators and “grafters,” housing, health care, and, of course, the struggles of the Dust Bowl migrants in California. Briley has gone directly to the newspaper source material, thereby introducing columns that would be unfamiliar to those who have relied only on the selections of 1975 compendium, Woody Sez.

Darryl Holter’s short essay on “Woody and Skid Row in Los Angeles” focuses on the few nuggets of Guthrie’s writing inspired by that location and its associations — “Skid Row Blues,” “Fifth Street Blues,” and extracts from “Woody Sez” and Bound for Glory. As Holter argues, the Skid Row experiences of Los Angeles, Stockton, Redding, and San Francisco had indisputably “left [their] mark on Woody Guthrie” (151) before his departure for New York, where he continued to delve into the bowels of urban degradation for some of his most potent imagery.

In “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” Bryant Simon and William Deverell chart the reimagining of Steinbeck’s seminal hero by the likes of Guthrie, Studs Terkel, Bruce Springsteen, and, most recently, “Bowery hipsters … going to Depression parties in loft apartments and showing up in wool hats like the one Joad — aka Henry Fonda — wore in John Ford’s film version of The Grapes of Wrath” (154). It is a chilling descent that Simon and Deverell describe, from Joad as awakened union activist to Joad as simply “a visual …the image of Depression chic”.

Josh Kun’s “Woody at the Border” is a fascinating discussion by one of the leading cultural historians of not only Los Angeles (Songs in the Key of Los Angeles and To Live and Dine in L.A., 2013 and 2015 respectively) but also popular music at large, most notably through his influential Audiotopia: Music, Race, and America (2005). Going well beyond the expected exploration of Guthrie’s brief broadcasting stint on XELO radio in Tijuana, Kun introduces an eye-opening correspondence between Guthrie’s “Deportee” of 1948 and the corrido “El Deportado” (“Deportee”) by Los Hermanos Bañuelos, recorded in 1930 and prefiguring Guthrie’s own rhetorical craft: “Goodbye, beloved countrymen, they are going to deport us. But we are not bandits — we came to work hard” (170). Guthrie is here situated in the great arc of “the music of migrancy” (172) from the early 1930s to today, when you can “tune in to L.A. stations like 105.5 La Que Buena and you’ll hear Tom Joad’s Mexican cousins, but also the ghost of Woody Guthrie himself”.

The concluding essay by Holter, a survey of Guthrie’s recordings from 1939 to 1949, drifts away from the central location of Los Angeles in order to give a whistle-stop tour of Guthrie’s entire recorded output as well as his recording legacy. Interested readers and listeners who wish to maintain the L.A. focus would do well to go to Holter’s own CD and DVD package, Radio Songs: Woody Guthrie in Los Angeles, 1937-1939 (2015), reviewed in the first issue of the Woody Guthrie Annual. – WILL KAUFMAN

Follow Darryl Holter Music

Recent Posts

Darryl Holter

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur. Darryl Holter is also a historian who has written on Woody Guthrie and a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.