Grown-Up Anger Darryl Holter Book Review

“I’ll Take You to a Place Called Italian Hall”: On Daniel Wolff’s “Grown-Up Anger” and the Calumet Massacre of 1913

Darryl Holter Book Review

Darryl Holter Book Review | Los Angeles Review of Books

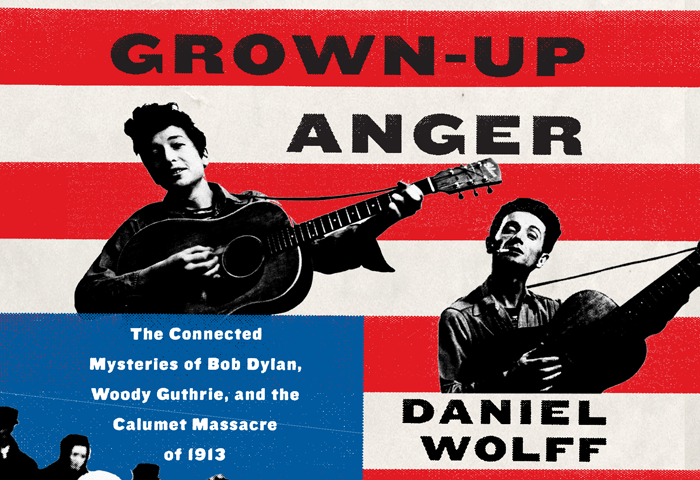

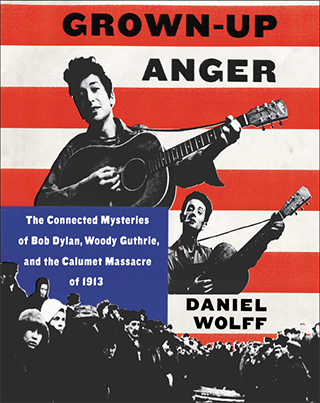

A LABOR STRIKE and a heart-wrenching tragedy in 1913, Woody Guthrie at a hootenanny in a New York basement in 1945, and Bob Dylan in a recording studio in 1962 — these three seemingly unrelated events provide the framework for Daniel Wolff’s study of industrial violence in the United States, the folk music revival, and the evolution of rock ’n’ roll. Wolff’s narrative is an angry polemic and social commentary. The “mysteries” he explores reveal how economic depression, foreign wars, and racial discrimination shaped the music of two restless and fiery artists. Along the way, he delves into the world of copper mining, revising the official version of the 1913 tragedy in order to set the record straight.

Darryl Holter Book Review: Grown Up Anger by Daniel Wolff

Labor disputes and industrial disasters are not particularly unusual events in American history, but the macabre deaths of 74 people (60 of whom were children between the ages of two and 16) on Christmas Eve in a tall, jammed stairwell of the Italian Hall in strike-ridden Red Jacket, Michigan, in 1913 (renamed Calumet in 1929) was no ordinary catastrophe. Several thousand underground copper miners, mostly Finnish and Italian immigrants, had been on strike for more than six months, but they were running out of strike funds and faced a powerful business-led Citizens’ Alliance. As Christmas drew near, the mining union’s Women’s Auxiliary organized a big Christmas party to make sure that every child of a striking miner would receive a holiday gift. Hundreds of children and parents climbed up the high steps to the second floor ballroom of the Italian Hall and gathered around a large Christmas tree. A young girl played a piano and the crowd quieted down to listen. Although there remains a dispute as to what happened next, it is clear that some person or persons yelled, “Fire!” and that this provoked a mad stampede for the stairwell. Many children tripped and fell headlong down the steep stairs, landing with broken bones in front of the doors. For some reason, the doors would not open. The strikers claimed the anti-union thugs hired by the Alliance held the doors shut; the Alliance later claimed the doors opened to the inside. As more and more tried to escape, the stairway became jammed with panic-stricken children who piled on top of each other, breaking their painfully entangled arms and legs. Soon they began to suffocate. When the doors were finally opened, 74 bodies were carried back up the stairs and laid in rows by the Christmas tree.

… Review Continued at at LARB Darryl Holter Book Review

The Keweenaw Peninsula is a 70-mile finger of land that juts into Lake Superior at the northernmost point of the state of Michigan. I stepped on the gas pedal and pushed my Chevrolet up to 55, heading south from Copper Harbor, the small town at the top of the peninsula. Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is physically separated from the rest of Michigan by the Straits of Mackinac and when you look at a map of the United States you might say, with perfect logic, that the Upper Peninsula really should be part of Wisconsin. Most of the UP is scenic northern forest, but wild, rugged, and largely undeveloped. I’m sure more wolverines live in the UP than humans, but they don’t get counted in the census. US Highway 41 is a six-lane freeway in Milwaukee, but up on the Keweenaw Peninsula it is a narrow two-lane road with tall pine trees standing like soldiers along the edge of the asphalt. Rounding a sharp turn, I suddenly saw five or six whitetail deer directly in front of me. I swerved and missed most of them, but one deer jumped in the same direction as my car, smashed into the hood, broke the windshield, flew over the top, and dashed into the forest. The car was not drivable. After a half hour or so, a Highway Patrolman pulled up to offer assistance. “It happens all the time,” he said. “There are a lot of deer and it can be hard to see them.” He called a tow truck and soon my damaged car was on its way to Snow’s Auto Repair in Calumet, Michigan.

Wolff contextualizes the story of 1913 in a comprehensive history of copper mining in the Upper Peninsula. Native Americans mined copper and used it to make hooks, knives, and jewelry. French explorers and Jesuit missionaries discovered new uses for copper, prospectors searched for more, and industrialists from the East invested large sums to go underground, recruiting thousands of immigrants from Wales, Russia, Italy, and Finland to drill and extract the ore. By reopening the historical record, Wolff resolves lingering mysteries about the tragedy:

Was there a fire? No.

Did someone actually yell “Fire!”? No one ever confessed to it.

Did the strikebreakers deliberately hold the door shut to prevent the children from leaving? No one claimed to have seen anyone hold the doors shut, although the strikers and their families were inside the building.

Did the doors at the bottom of the steps open to the inside, as is so often repeated in official descriptions of the tragedy? No.

It is these rumors and uncertainties that have passed for history, burying the truth under layers of obfuscation that anger Wolff and have led him toward Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan. Woody Guthrie wrote (and rearranged) about 1,500 songs, but “1913 Massacre,” with its dark tone, solemnity, and dirge-like tempo, was a uniquely powerful piece of his repertoire. The dry humor and ironic double meanings often found in his compositions are jettisoned as Guthrie reports on the shockingly brutal facts in a matter-of-fact way. It suggests that the full extent of the horror sapped him of emotion. As Wolff correctly notes, we hear nothing about socialism or revolution or even unionism. Instead, Guthrie takes the listener along with him as an observer, a witness to what will unfold. “Take a trip with me back in 1913,” writes Guthrie.

Calumet, Michigan, in the copper country.

I will take you to a place called Italian Hall,

where the miners are having their Christmas ball.

I will take you in a door and up the high stairs,

singing and dancing is heard everywhere,

I’ll let you shake hands with the people you see,

and watch the kids dance around the big Christmas tree.

Guthrie crafted the song based on a memoir written by “Mother” Mary Bloor, an early Socialist and labor organizer well known in political circles for her courage in the face of repression and violence. Bloor’s daughter, Herta Geer, was the wife of Will Geer, the actor and political activist who had befriended Guthrie in Los Angeles in 1939 and introduced him to the local writers, actors, and musicians involved in the growing labor movement and the fight against fascism. Guthrie wrote the song in 1945, about five years after Bloor’s 300-page memoir, We Are Many, appeared. Although her section on Calumet is only a few pages long, it was crammed with detail, much of which Guthrie incorporated into his song.

Bob Dylan

Wolff uses “1913 Massacre” as an entry point into Guthrie’s life. Despite Guthrie’s self-created persona as the “Political Okie,” with his deliberate misspellings, improper grammar, and “aw shucks” demeanor, Guthrie was not an uncomplicated personality. As he writes his narrative of “1913 Massacre,” Wolff draws out some of those complexities. On the one hand, Guthrie’s situation in 1945 was more stable than ever. He had completed his military service and several tours in the Merchant Marine, and had survived a torpedoing. Working with Moe Asch he was recording scores of songs and beginning a new project called “American Documentary,” which he described as “a kind of musical newspaper,” using songs to illuminate and comment upon current events. His semi-autobiographical novel, Bound for Glory, had received 150 mostly positive reviews and encouraged Guthrie to begin a second novel, Seeds of Man. A song he had written in Los Angeles in 1939, “Oklahoma Hills,” recorded by his cousin Jack Guthrie, reached number one on the folk jukebox list in 1945. That same year, along with Pete Seeger and others, he founded People’s Songs. The United States and the Soviet Union remained united against the Axis powers, unions had made unprecedented progress during the war years, and organized labor emerged for the first time as an important political force at the national level.

… Review Continued at at LARB Darryl Holter Book Review

Woody Guthrie

Woody Guthrie appealed to KFVD radio listeners in Southern California and found a new audience among political activists, union organizers, and progressive writers who had never seen a bona fide Okie with left-wing politics. He cultivated his persona in songs, newspaper articles, and Bound for Glory. Even as he branched out into new areas, such as children’s song, Jewish songs, and novels and cartoons, the Okie persona never left him.

Wolff contrasts this with Bobby Zimmerman’s constant reinventions of himself. First the artist who would be Dylan abandoned his early interests in rock and blues for the emerging folk scene and changed his last name. Then, after discovering some Guthrie records from one of his folkie friends in the Dinkytown section of Minneapolis, he immersed himself in the Guthrie persona. He learned all of Guthrie’s songs and limited his performances at coffee houses and parties to the man’s repertoire. He mimicked Guthrie’s guitar style, speech patterns, and clothing. He carefully read Bound for Glory and began to create tall tales about his background, claiming that he was from Albuquerque or Gallup or Illinois — anywhere but Hibbing, Minnesota. “Dylan made himself authentic,” writes Wolff.

He changed who he was to get closer to the truth. Or try to. The sound that eventually came over pop radio — his timed drawl, the rural edge, the off-center sense of humor — was a lot Guthrie. That’s how Dylan became an original — through imitation. It’s as if he ran from his middle-class, mid-20th-century Hibbing and went back to Guthrie’s ’30s. Or as he put it, “I was making my own depression.”

Veteran folkies from the Dinkytown scene who were familiar with Guthrie chided Dylan for going too far with his impersonation. So Dylan went east to find Guthrie, claiming that he hopped freight trains and hitchhiked like Woody, when he actually got a ride from a friend. Dylan’s visits with a dying man in Greystone Hospital have been treated elsewhere, but Wolff captures an important element of this encounter. While Dylan was performing Guthrie’s songs for his idol, who was no longer able to speak, he confronted the reality that Guthrie was effectively gone, that his world of the Depression and his war against fascism had disappeared, that his fervent political dreams had vanished in the wind. Later Dylan would write:

Woody Guthrie was my last idol

he was the last idol because

he was the first idol

I’d ever met

that taught me

face t’ face

that men are men

shatterin’ even himself

as an idol …

Dylan’s confrontation with Guthrie’s demise was the starting point for Dylan’s composition of “Song to Woody,” written only a few days after their first meeting.

… Review Continued at at LARB Book Review by Darryl Holter

¤

Darryl Holter Book Review:

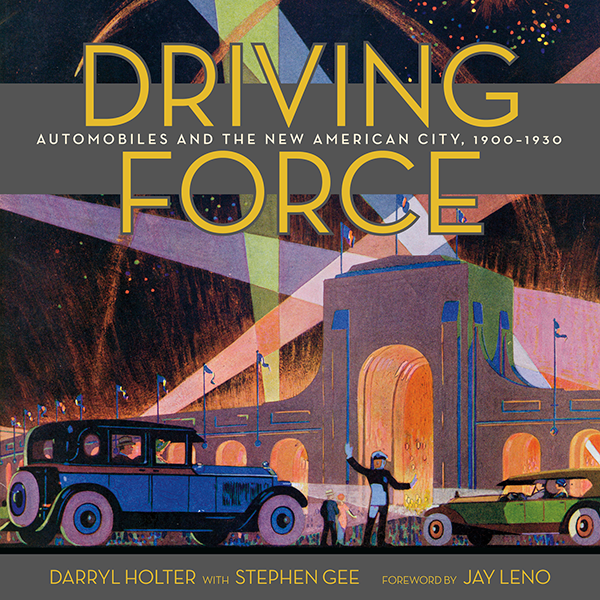

Darryl Holter is a historian, entrepreneur, musician, and owner of an independent bookstore. He has taught history at the University of Wisconsin and UCLA and is an adjunct professor at USC.

Read Article at LARB

Follow Darryl Holter Music

Recent Posts

Darryl Holter

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur. Darryl Holter is also a historian who has written on Woody Guthrie and a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.