A Tale of Two States Darryl Holter Book Review

A Tale of Two States

Darryl Holter Book Review

Darryl Holter Book Review | Los Angeles Review of Books

TWO STATES, two directions, two futures.

Dan Kaufman, author of The Fall of Wisconsin: The Conservative Conquest of a Progressive Bastion and the Future of American Politics, and Manuel Pastor, author of State of Resistance: What California’s Dizzying Descent and Remarkable Resurgence Mean for America’s Future, have crafted lengthy subtitles that reveal their books’ basic story lines. Both books chronicle dramatic swings from one side of the political spectrum to the other, and both highlight the ways in which state-level politics can influence policy at the national level. Both authors go behind the scenes to show how elected officials are influenced not only by their constituencies and the political media but also by obscure lobbying groups with names like the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment, the American Legislative Exchange Council, the University of California Center for Labor Research and Education, the Bradley Foundation, and the KochPAC. Perhaps the authors’ most significant contribution may be to offer voice to the dozens of local activists of all political stripes who are the connective tissue between the political elites and the voting public.

If your political compass swings toward the left, the portrait Kaufman paints of Wisconsin today is painful. After all, this is the state that brought us the first workers’ comp and unemployment compensation legislation, collective bargaining for public employees, child labor laws, progressive income tax, and the “Wisconsin Idea” of a first-rate university system whose research mission is to serve the public interest. These various initiatives made Wisconsin into a “laboratory for democracy” and served as a model for the federal policymakers who crafted New Deal reforms, including Social Security, the National Labor Relations Act, and the Fair Labor Standards Act.

Scott Walker, a Milwaukee County executive who rode the Tea Party wave in 2010 to become the state’s governor, has devoted his tenure to dismantling this democratic project. After a few weeks on the job, Walker introduced a “budget repair bill” that demanded “sacrifice” from public employees at the state and local levels. Costs were reduced by forcing workers to surrender half the amount of their pensions while doubling the amount they pay for health care. Collective bargaining was scaled back, and wage increases were capped at the rate of inflation. Union dues were made voluntary, which allowed employees to receive the benefits of union negotiations without paying for them. Employees were required to recertify their unions every year.

Walker’s bill, known as Act 10, provoked spontaneous protests around the state, especially in Madison, where 1,000 protesters, led by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Teaching Assistants’ Association, marched on the state capitol. They were joined, the next day, by thousands of others, including hundreds of high school students. The result was an impromptu occupation of the capitol rotunda, as protesters sought to prevent action on the bill until local pressure could be brought to bear on Republican legislators. As the crowds grew day by day, Walker — who needed a quorum of senators to advance the bill — sent police officers to the homes of Democratic senators to arrest them and bring them to Madison for the vote. Fourteen Democrats fled to Illinois to allow more time for public opposition to build. Protesters continued to occupy the capitol for three weeks. Eventually, over objections from Democratic Senator Peter Barca, who had stayed in Wisconsin, the new bargaining bill was advanced to the floor, where it passed both houses within hours. The action closed the door on the “laboratory of democracy” and opened the floodgates to a wave of conservative legislation to dismantle unions, restrict voting rights, move funds from public to private education, and repeal environmental laws.

While Walker’s victory over unions made him a darling of the right and catapulted him onto the national stage and into a run for the presidency in 2016, behind-the-scenes forces sowed the seeds for his success. The Milwaukee-based Bradley Foundation, for example, distributes tens of millions of dollars to right-wing think tanks, litigation centers, and opposition research groups around the country; the organization’s president, Michael Grebe, served as the head of Walker’s gubernatorial campaign in 2010. Then there is the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a nonprofit begun in Chicago by conservative activist Paul Weyrich that specializes in producing model legislation aimed at weakening unions and environmental laws, funding private education with public funds, and restricting voting rights. ALEC counts among its members one-fourth of all state legislators in the nation; the group has deep roots in Wisconsin beginning in the 1980s with former governor Tommy Thompson, who also served as Secretary of Health and Human Services under George W. Bush. Another ALEC adjunct, the State Policy Network, provides slanted research and talking points for conservative state legislators. Walker used ALEC’s model bills in shaping his policy toward unions, the environment, public education, and voting rights.

The labor movement and the Democratic Party fought back by launching recall elections against Republican senators in Wisconsin. After having success in two of these recalls, they began a campaign against Walker himself. This was the first election held after the Supreme Court’s landmark Citizens United decision, in which the conservative majority lifted restrictions on campaign financing. Seeking to protect their new hero, right-wing groups and wealthy individuals pumped huge funds into battling the recall effort. Nearly $140 million flooded into the state during the election, $81 million alone for the Walker recall. In a relatively cheap media market, the Koch Brothers bankrolled a barrage of very effective ads (a man fishing says, “I didn’t vote for Scott Walker, but I’m definitely against this recall”) that gave many Wisconsinites — who had grown weary of the acrimonious arguments that split families, neighbors, and co-workers — a reason to vote no. In the end, Walker survived, 53 to 46 percent.

Kaufman is at his best when introducing us to the local activists and legislators who won’t be heard on CNN or Fox or quoted in The New York Times. I was particularly taken with the story of Chris Taylor, a state legislator who infiltrated ALEC and reported on its doings. Randy Bryce, the union ironworker whose campaign for Paul Ryan’s seat helped push the GOP Speaker into early retirement, also has a compelling story. And it was a personal pleasure to read quotes from legislators I knew from my lobbying days in Madison more than 25 years ago. Even more arresting were the sage comments of one of my former history students at the University of Wisconsin, David Poklinkoski, who went on to become president of the Brotherhood of Electrical Workers at Madison Gas and Electric.

What’s missing from The Fall of Wisconsin is a strategic sense of how progressives can build alliances and coalitions capable of creating a new majority to overcome the formidable obstacles erected by Walker and his crew. How can the people in Wisconsin who voted for Trump be lured back to the Democratic column? How can progressives win in rural districts? How can unions that have been forced to become voluntary organizations find a path to power in the workplace? These are big, hard questions, of course, but Kaufman largely ducks them. Kaufman does demonstrate, in depressing detail, how the constellation of conservative think tanks, political action committees, and politicians have reshaped Wisconsin society in a way that conforms to their political ideology: weaker unions, no wage growth, rising child poverty, a smaller middle class, deep cuts in K–12 and university education, and voting restrictions that exclude an estimated 11 percent of the electorate. The former “laboratory of democracy” is now the harbinger of a new and very different United States of America.

Manuel Pastor, in his book on politics in California, State of Resistance, provides a very different perspective. After World War II, California offered the world a new version of the American Dream, with plentiful jobs, affordable homes, a vibrant education system extending from kindergarten to graduate school, an expansive infrastructure of superhighways and state parks, and a relatively tolerant attitude toward ethnic and cultural diversity. Then came a new set of problems that slowly turned the California dream into a nightmare: racial unrest, tax revolts, unstable state finances, political gridlock, the loss of millions of jobs (including “nearly half of the nation’s net job loss” during the recession of the early 1990s), and a sharp rise in anti-immigrant attitudes. Pastor chronicles the historical signposts of this “dizzying descent”: police violence, the Watts riots, and white flight to the suburbs; Governor Reagan’s campaign against student protesters and state spending on higher education; Nixon’s “Southern Strategy,” which lured whites away from the Democratic Party; decisions by the California Supreme Court that disconnected local spending on schools from local property taxes, angering white voters who felt that “their” taxes were not funding schools for “their” children; “Immigrant Shock” as the percentage of foreign-born people residing in California grew from 13 percent of the United States’s total foreign-born population in 1960 to 33 percent in 1990; and ballot initiatives, beginning with Prop 13 in 1978, that required a supermajority vote in the state legislature to raise taxes, creating a never-ending fiscal crisis.

These ballot initiatives — direct up-or-down votes by the electorate — began as progressive measures meant to ensure the peoples’ will against an unresponsive legislature, but they turned into something quite different during this period. It was simple arithmetic: limit the ability of the legislature to raise revenue, putting the matter in the hands of older, predominately white voters, who were more likely to vote in off-year elections. As Pastor notes, “Nearly the same number of initiatives were passed in the eighteen years between 1978 and 1996 as in the sixty-seven years between 1911 and 1978.” The blizzard of ballot initiatives that began with Prop 13 continued with Prop 165, which would have reduced state welfare payments, although it failed; next came Prop 187, a measure to deny all public benefits to undocumented workers. Running for governor in 1994, then-Governor Pete Wilson trailed his Democratic opponent by 23 points; he shifted his position to support Prop 187 and sailed to victory. Prop 184 was the famous “three strikes” initiative designed to get tough on criminals; it won by a mile. Prop 209 outlawed affirmative action in state hiring and university admissions, while Prop 227 banned bilingual education in public schools. Prop 226 would have limited the power of unions, but it was defeated. ( … Review Continued at at LARB Book Review by Darryl Holter)

¤

Darryl Holter Book Review:

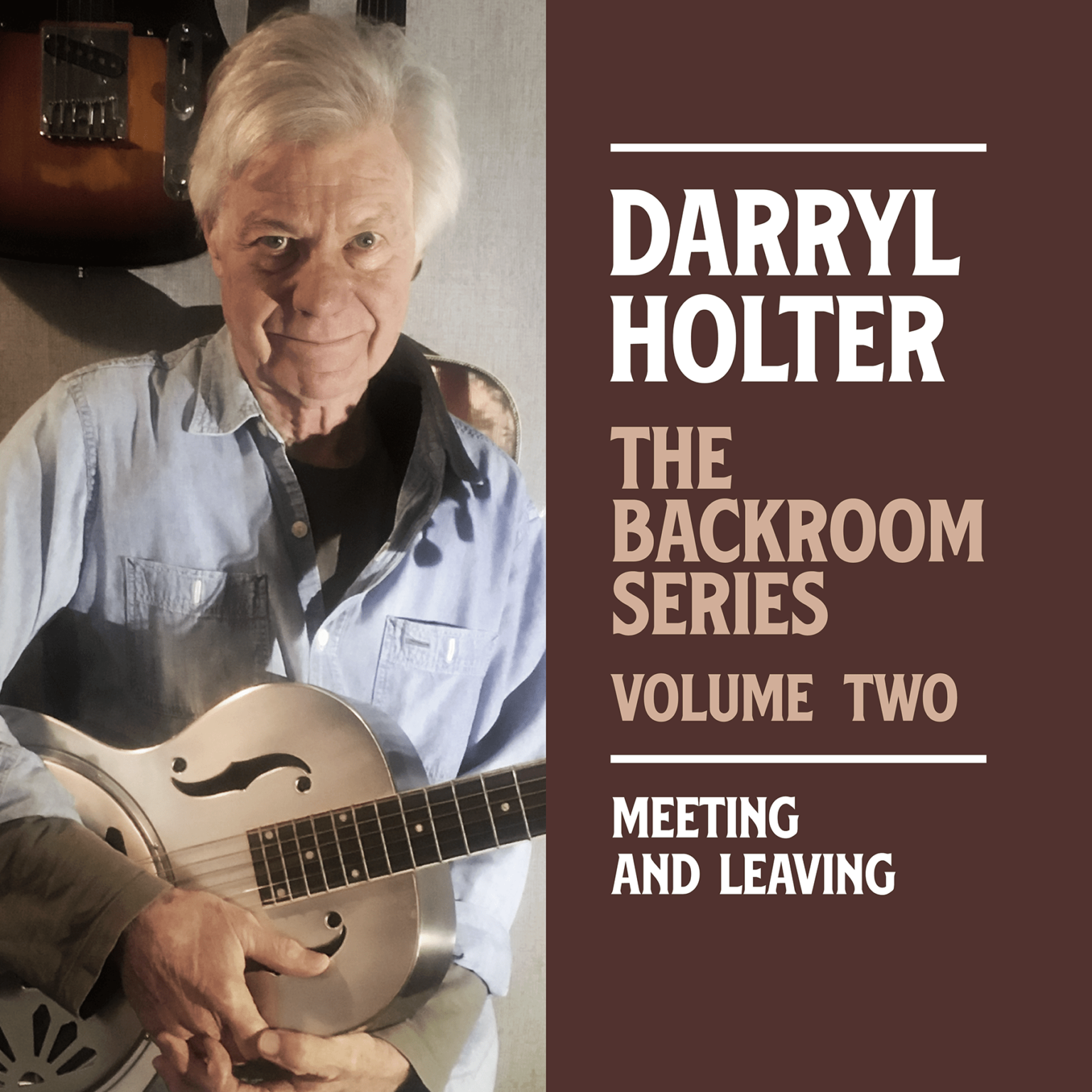

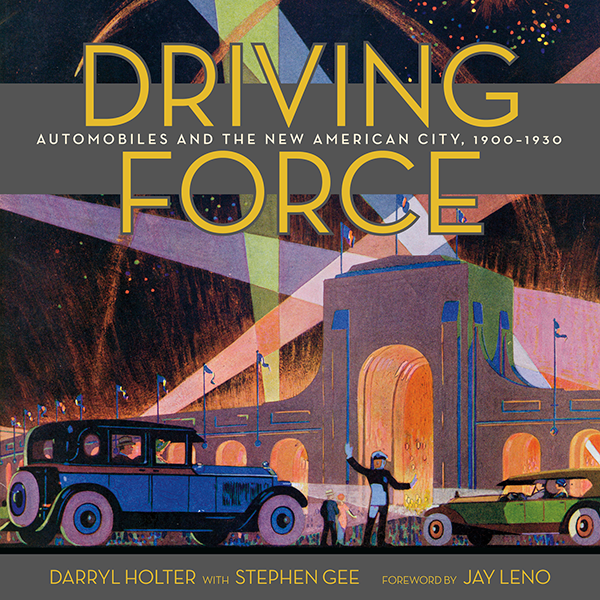

Darryl Holter is a historian, entrepreneur, musician, and owner of an independent bookstore. He has taught history at the University of Wisconsin and UCLA and is an adjunct professor at USC.

Read Entire Article at LARB

Follow Darryl Holter Music

Recent Posts

Darryl Holter

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur. Darryl Holter is also a historian who has written on Woody Guthrie and a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.