On the passing of Spider John Koerner

I was really saddened to learn that John Koerner had died. He was an extremely talented guitarist and folksinger who was a mentor to young Bob Dylan and a fixture in the music scene in Minneapolis, especially on the West Bank (of the Mississippi River). John was the last of the original three-some (including Dave Ray and Tony Glover) that recorded the path-breaking “Blues, Rags, and Hollers” album. He was low-key and down-home in a quiet Minnesota way, but he was very accessible, and I used to see him a lot and talk with him frequently when I lived on the West Bank. Years later, when I played at one of the West Bank music bars in Minneapolis to promote my album, “West Bank Gone”, I met with John.

One night when John Koerner had finished a set at the Triangle Bar and opened a bottle of Schmidt Extra Special, I said, “Hey, John, lately it seems like you’re playing all your songs at the same speed, with the same beat all the time and they are starting to sort of like sound all the same.” “That’s deliberate,” he said. “It’s easier for me to remember how to do them if I do them all the same. I’ve been trying to do this for years and it’s finally working.” That was the way he talked. He told odd jokes in this laconic way: A sixteen-year-old boy had never spoken in his life. One morning he sat down to breakfast with his parents. His mother served up some oatmeal. The boy took one spoonful and then made a face and spit it back into the bowl. “This oatmeal takes like shit!” he exclaimed loudly. His parents were incredulous for he had never before uttered a word. “Son, you’ve never spoken before. Why did you wait until now to say something?” The boy answered, “Up ‘til now everything was good.”

I really liked John’s song “I Ain’t Blue” which was recorded by Bonnie Raitt at Dave and Sylvia Ray’s studio outside of the city. At one point in the early ‘70s, I think, John decided to stop singing his old Delta blues songs that most of us were familiar with. He switched to old traditional American folksongs but used his familiar foot-stomping to give the songs a little more oomph. I thought his album, “Running, Jumping, Standing Still” with Willy Murphy was a break-through album, very different from his earlier work. Ever since I heard that album I’ve been playing “Friends and Lovers”—a great song. In those days, walking around the West Bank at night you would hear some of the songs being played in peoples’ apartments. But it was hard to compete with other blockbuster “concept” albums of the time like the Beatles White Album and the Stone’s Satanic Majesties or whatever it was called.

– DH

About Darryl Holter

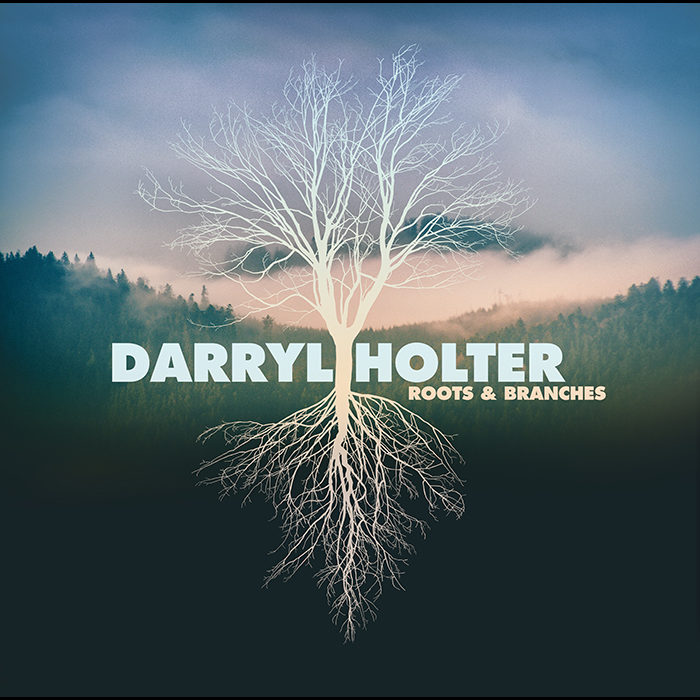

Darryl has recently released his new Roots & Branches album .

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. As a child, his early influences were Elvis and Johnny Cash, then Bob Dylan, then the folk-rock and country-rock. His current brand of Americana Music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events. In 2008 he formed 213 Music and launched his first self-titled album of original songs. Two years later he released “West Bank Gone,” an album that highlighted the West Bank (of the Mississippi River in Minneapolis) music scene in the 1970s. Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur.

Historian

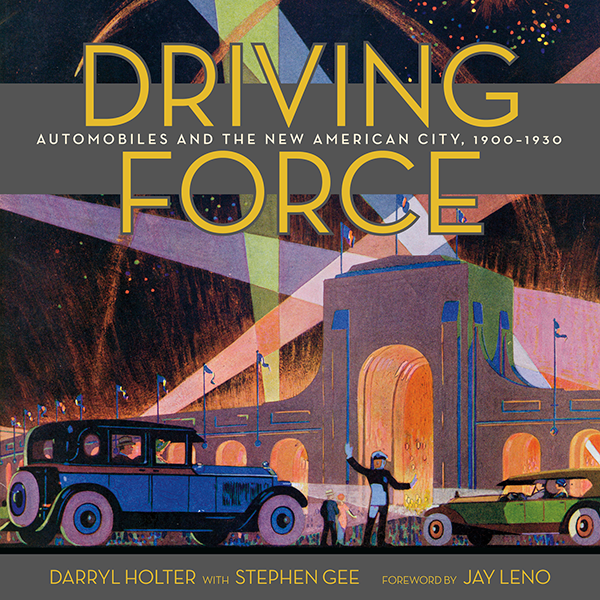

Darryl Holter is also a historian who has written on Woody Guthrie and a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Follow Darryl Holter Music

Recent Posts

Darryl Holter

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur. Darryl Holter is also a historian who has written on Woody Guthrie and a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.