Darryl Holter Reviews 26 Songs in 30 Days: Woody Guthrie’s Columbia River Songs and the Planned Promised Land in the Pacific Northwest. for Woody Guthrie Annual

The Woody Guthrie Annual is an open-access peer-reviewed journal containing the most up-to-date scholarship on Woody Guthrie, his work and his cultural and political significance. The journal is published once a year, between June and December.

In addition to peer-reviewed scholarly articles, The Woody Guthrie Annual contains book and record reviews, news, and notices of relevant events. The journal is comprehensively indexed and archived in the appropriate online repositories. For more information on the life and legacy of Woody Guthrie, please visit www.WoodyGuthrie.org

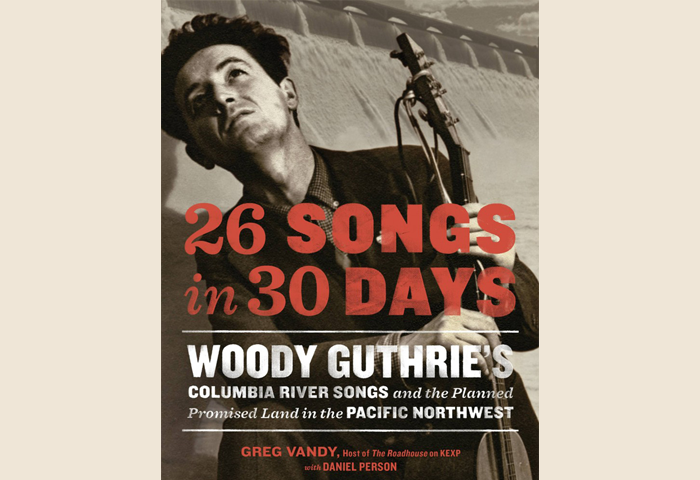

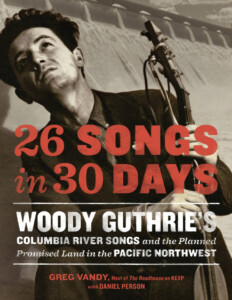

Greg Vandy with Daniel Person, 26 Songs in 30 Days: Woody Guthrie’s Columbia River Songs and the Planned Promised Land in the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 2016. Hardcover, $24.95.

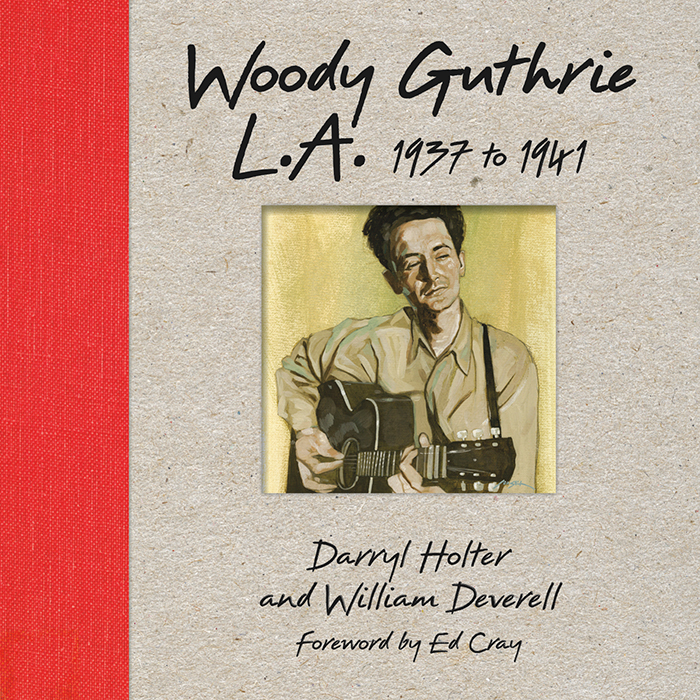

Reviewed by Darryl Holter

We know about Woody Guthrie’s early years in Okemah and Pampa, his formative political and musical development in Los Angeles, and his later years spent in New York City. Much less is known about his remarkably productive one-month stint in the state of Oregon in 1941. Guthrie was h i r e d b y t h e Bo n n e v i l l e P owe r Administration (BPA) in Portland, Oregon, where the US Department of the Interior was constructing the massive Grand Coulee Dam project on the Columbia River. The job involved writing a group of songs to be used in a documentary film to promote hydro-electrical power. Although the job was supposed to last an entire year, Stephen Kahn, the administrator who had written Guthrie about the job (on the recommendation of Alan Lomax), decided that reclassifying the job as an “emergency appointment” for a single month would not require a security check by the Civil Service Commission. Kahn was not wrong: J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI were on Guthrie’s trail by the time he completed the job, but Guthrie had moved on before his hiring could be prevented. Kahn gave Guthrie a few books, asked him to tone down his politics, shepherded him through the BPA bureaucracy, and found a committed employee, Elmer Buehler, to drive him around the region. Guthrie recorded twenty-six songs in the basement studio of the BPA and was paid $266 for his efforts.

Biographies by Joe Klein and Ed Cray devote only a few pages to this exciting, if brief, episode in the Guthrie saga. A lack of archival material, primary documents, and the original recordings limited their research. Guthrie himself, somewhat uncharacteristically, wrote very little about his experiences in Oregon. Later, when he worked with Pete Seeger and Alan Lomax to compile more than 200 songs, including dozens of Guthrie compositions, for Hard Hitting Songs for Hard-Hit People in 1947, Guthrie did not include any of the songs from the Columbia Collection.

Greg Vandy, with the help of Daniel Person, fills in the gap with 26 Songs in 30 Days: Woody Guthrie’s Columbia River Songs and the Planned Promised Land in the Pacific Northwest. Vandy, a radio presenter who hosts a roots music show called Roadhouse on KEXP in Seattle, is well equipped to deliver this story because of his knowledge of folk music and the local history of the Pacific Northwest. In this well written and creatively illustrated book, Vandy shows how Guthrie moved beyond his Dust Bowl ballads to embrace a New Deal vision of a bright new future based on technological progress and economic planning by bringing “electric power to the people” and using nature’s abundant water source to provide irrigation that could transform unemployed workers into productive farmers.

Greg Vandy, with the help of Daniel Person, fills in the gap with 26 Songs in 30 Days: Woody Guthrie’s Columbia River Songs and the Planned Promised Land in the Pacific Northwest. Vandy, a radio presenter who hosts a roots music show called Roadhouse on KEXP in Seattle, is well equipped to deliver this story because of his knowledge of folk music and the local history of the Pacific Northwest. In this well written and creatively illustrated book, Vandy shows how Guthrie moved beyond his Dust Bowl ballads to embrace a New Deal vision of a bright new future based on technological progress and economic planning by bringing “electric power to the people” and using nature’s abundant water source to provide irrigation that could transform unemployed workers into productive farmers.

The back story of this episode is how a handful of resourceful people uncovered lost documents and undiscovered recordings that allowed Vandy to flesh out the details in finer relief. Working in the public information office of the BPA in 1979, Bill Murlin, who had tinkered with folk music during his college days in the 1960s, did a double take when he stumbled upon an old 16-mm film called The Columbia, which listed Woody Guthrie in the credits. Intrigued, Murlin combed through BPA records in Portland and Seattle but found little of value. He wrote to folklorist Richard Reuss, who had compiled the most up-to-date bibliography of Guthrie, to ask about the possible existence of Columbia River recordings. Reuss replied that none were in existence, but he did send a copy of a letter from Bess Lomax, who, along with her brother Alan, had recorded Guthrie in 1940, and attached to the letter were the manuscripts of twenty-four of the twenty-six songs.

Murlin’s request to make a documentary film on the Guthrie songs was rejected by the BPA, but several years later he was granted permission to compile a songbook to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the BPA. Unable to find anything about Guthrie in the BPA archives, Murlin sent a letter to retired employees of the agency asking for information about the Guthrie recordings. He struck pay dirt when Ralph Bennett, a former BPA official who in 1947 had invited Guthrie to come to Spokane as his guest at the convention of the National Rural Electrical Cooperative Association, reported that he had acetate copies of the original songs recorded in the basement of the BPA headquarters. A final important document was uncovered when Murlin, aware of a government regulation that employee records were to be kept for fifty years before being destroyed, traveled to the central depository of the National Archives in St. Louis in 1991 to ask if Guthrie’s employment file still existed. According to Murlin, the file was nearly on the conveyor belt of the shredding machine when he retrieved it. Guthrie’s Application for Employment, reproduced by Vandy, is eyeopening. We learn that Guthrie weighed 125 pounds, had completed the tenth grade, and for the last decade had worked as a night clerk, porter, sign painter, truck delivery driver, guitar player in a cowboy band, and radio host.

Despite Murlin’s success in uncovering these lost materials, some documents relating to Guthrie — including the original basement recordings, the raw footage of The Columbia, and original recordings that Kahn made in New York for the film soundtrack — had been destroyed in the 1950s. Elmer Buehler, who had driven Guthrie around the region, was later ordered by BPA management to burn all twenty-five copies of The Columbia. But he hid two copies in his basement and brought them out in the 1970s to give to an Oklahoma film historian, Harry Menig, who wanted to screen the film.

The Columbia River songs reveal Guthrie’s excitement with the beauty of the landscape, the huge scope of the electrification project, and its promise to improve the lives of working people of the valley. Fourteen of the songs were originally written and recorded in Oregon in 1941. Five more were written in Oregon but never recorded. The remainder were older songs submitted by Guthrie (and slightly revised in some cases) to meet his quota of twenty-six songs. As with most Guthrie compositions, all the songs relied on traditional or otherwise borrowed melodies. Several songs later became Guthrie favorites, including “Grand Coulee Dam,” “Hard Travelin’”, and “Roll on, Columbia,” eventually adopted as the Washington state folksong. “Grand Coulee Dam” includes wonderfully poetic and nearly tongue-twisting phrases: “In the misty crystal glitter of the wild and windward spray” and “Like a prancing, dancing stallion down her stairway to the sea.”

Another well known Guthrie song, “Pastures of Plenty,” describes the difficulties faced by migratory workers who moved further up the Pacific coast in search of agricultural work (“We travel with the wind and the rain in our face, / Our families migrating from place to place”) and a brighter new future enhanced by the massive hydro-electric project (“One turn of the wheel and the waters will flow / ‘Cross the green growing field, down the hot thirsty row…. / The Grand Coulee showers her blessings on me, the lights for the city, for factory, and mill”). By contrasting the struggles of a Dust Bowl past with an electrically-charged future amidst “Pastures of Plenty,” Guthrie’s Columbia River collection offers an element of optimism not apparent in his first commercial album, Dust Bowl Ballads.

Vandy suggests that the Oregon experience, if brief, marked an important transition in Guthrie’s musical development as he moved beyond his staple of Dust Bowl songs from the Los Angeles years. Through his involvement with Pete Seeger and the Almanac Singers, the CIO organizing activities, and playing with African American musicians, Guthrie soon began to broaden his focus. Even as he penned the lyrics to “Hooversville,” a scathing critique of unemployment and homelessness, a few days before leaving Los Angeles for Portland, he must have been aware that the “rickety shacks” and “rusty tin” shanties of California’s Hoovervilles were already emptying, as thousands of the Dust Bowl refugees found new jobs in rapidly growing defense industries that were springing up in the industrial suburbs of Los Angeles. Guthrie also experienced an important transition in his personal life, as his marriage with Mary Guthrie finally collapsed after years of difficulties. When Guthrie left Oregon to return to New York, Mary stayed behind with the three children and later returned to Los Angeles.

Thus, with 26 Songs in 30 Days, Greg Vandy fills a gap in our knowledge of Guthrie’s development and contributes to our understanding of his influence on American music and culture. Particular mention should be made of the large number of powerful and rare images that are presented in black and white and color: photos, flyers, WPA posters, hand-written letters, typed song lyrics, cartoons, and album covers. The result is a beautiful book that deserves to be read, observed, and left on your coffee table for friends to see.

– DARRYL HOLTER