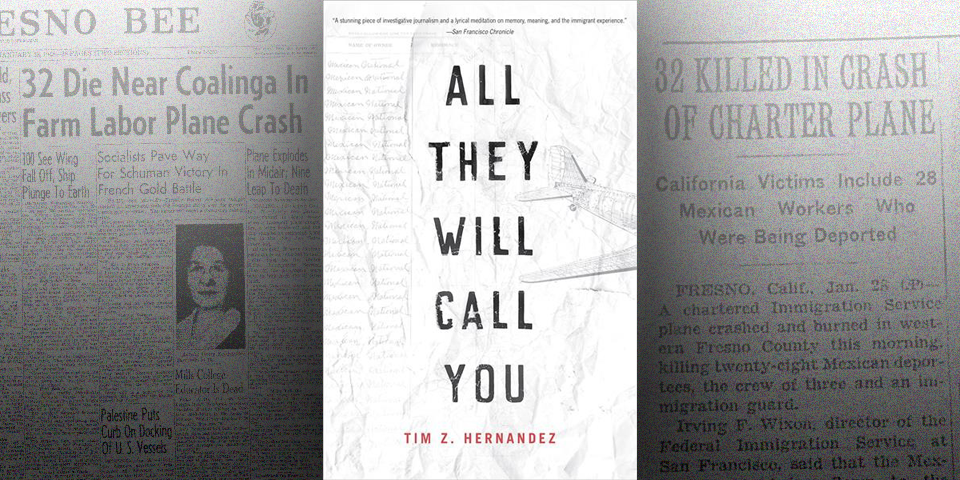

Tim Z. Hernandez, All They Will Call You: The Telling of the Plane Wreck at Los Gatos Canyon.

University of Arizona Press, 2017.

Book Review by Darryl Holter | Woody Guthrie Annual, 3 (2017)

Woody Guthrie made lists. He compiled lists of all the songs he had written and then made new lists, sometimes changing the titles. In private notebooks he made lists of songs he wanted to write, headlines from newspapers, and names of friends he planned to write. On New Year’s Day in 1943 he recorded a list of thirty-three resolutions including “work more and better,” “change socks,” and “dance better.” In Bound for Glory he compiled a long list of the types that populated Skid Row in Los Angeles (“stealers, dealers, sidewalk spielers, con men, sly flies, flat foots, reefer riders…”) — eighty in all! In 1941, reacting to the sinking of the USS Reuben James by a German submarine, Guthrie wrote a song for the Almanac Singers that memorialized the dead by listing all 115 names of the American sailors who had lost their lives at sea. Other members of the group argued that the song would be too long and an alternative version was created with a chorus that asked a question: “What were their names, tell me, what were their names? Did you have a friend on the good Reuben James.”

But Woody was never able to compile a list of the Mexican workers who had perished in a plane crash near Fresno, California in 1948. He learned of this tragic event from a brief AP story headlined “32 ARE KILLED IN CALIFORNIA PLANE CRASH: Mexican Deportees, Crew, and Guard Victims in Coastal Range Disaster.” The tragedy was bad enough, but what bothered Guthrie the most was the fact that the victims, Mexican workers hired for agricultural work in the Bracero program who were now being shuttled to a deportation center, were left nameless, faceless, apparently unimportant, quickly forgotten, and simply dismissed as “deportees.”

It took Guthrie only a few days to compose his first version of “Los Gatos Plane Wreck,” pounding out the lyrics on a typewriter with the caps lock pushed so the words leapt off the page, screaming, in upper case letters:

I DIED IN YOUR HILLS, I DIED IN YOUR DESERTS

I DIED IN YOUR VALLEYS, I DIED IN YOUR PLAINS

I DIED UNDER YOUR TREES, I DIED UNDER YOUR BUSHES

BOTH SIDES OF THE RIVER I DIED JUST THE SAME

Guthrie added a chorus that gave names to the nameless:

GOODBYE TO YOU JUAN GOODBYE ROSALITA

ADIOS MIS AMIGOS JESUS Y MARIA

He closed the song by asking a sad and painful question:

WHO ARE ALL THESE FRIENDS ALL SCATTERED LIKE

DRY LEAVES?

And he answered:

I’VE NOT GOT MY NAME AS I RIDE MY BIG AIRPLANE

ALL YOU CALL ME IS JUST ONE MORE DEPORTEE

Tim Hernandez, a poet and novelist born and raised in the San Joaquin Valley, took it upon himself to answer Guthrie’s question. He spent a full year painstakingly searching for the actual names of the victims. He visited the site of the crash and interviewed a handful of folks who had witnessed the horrifying event sixty years ago. Hernandez combed through municipal records, church directories, and newspapers. He tracked down relatives in the US and Mexico, and with their help was finally able to identify accurately the full names of all the Mexican laborers. And he answered the question posed by Woody decades earlier. But Hernandez was not satisfied with listing the names on a piece of paper. He organized a movement to memorialize the dead by drumming up political, financial, and religious support in a tireless campaign that culminated in 2013 with the unveiling of a beautiful granite headstone bearing all the names of the victims in a cemetery near the site of the crash.

Hernandez then took his project into entirely new directions — all of which add greatly to our understanding of one of the most powerful protest songs of the twentieth century. In Arizona, Hernandez tracked down information about the person who had composed the melody for Guthrie’s “Los Gatos Plane Wreck.” Martin Hoffman, a college student who followed the folk music scene and collected songs, had come across Guthrie’s poem and decided to put it to music. He drew inspiration from Mexican “ranchera” songs, with their common themes of loss and sorrow, and he built the song on the three-quarter signature so typical of a ranchera valseado. He altered the lyrics gently to fit the melody and shifted the voice from first to second person. With a friend named Dick Barker, Hoffman recorded the song in 1957 at Dick’s small apartment in Fort Collins, Colorado. He labeled the song “Deportees.”

The story might have ended then and there, but for the fact that Pete Seeger traveled to Fort Collins in 1958 for a concert attended by Hoffman and organized by the members of his local Ballad Club. Seeger was picked up from the airport and driven to campus by Club members. Following the concert, Hoffman invited Seeger and Club members to his small house to share songs. After several songs were performed and records were heard, Seeger, travel- weary and falling asleep, opened his eyes when he heard Hoffman sing his “Deportees” song. Seeger asked Hoffman to start the song again. He took out his pen and began to jot down the notations of the song in his notebook. Several months later, Hoffman received a letter indicating that Seeger had recorded the song and requesting that Hoffman sign documents that credited him with the music.

With this information, Hernandez traveled to Beacon, New York, to visit Pete Seeger and to ask Guthrie’s elderly comrade about the song. In discussing “Deportee,” Seeger was not certain of where Woody had found the song’s melody, since Guthrie almost always drew upon older melodies. But when Hernandez clarified that the melody had been written by Martin Hoffman, Seeger recalled instantly the night when he first heard the song. He also remembered that he had told his publisher, Harold Leventhal, to be sure to credit Hoffman with the music. And sadly, Seeger recalled that Martin Hoffman had taken his own life in 1971. And Pete became quiet until Hernandez continued the conversation:

“Would you like to hear Marty sing that song again?” I asked.

“Do you have a recording of it?”

“I do. Martin first recorded the song in his living room in 1957, with his friend Dick, when they were students.”

“Is that a recording machine?’

“It’s an MP3 player; it holds the music.”

Pete put the headphones on and cupped his hands over his ears to listen. I pressed play. He shut his eyes and began mouthing the lyrics to the song. He did this the entire three minutes and fifty-six seconds. When the song ended, he tugged the headphones slowly off of his ears. “Extraordinary,” he whispered.

Seeger’s recording of Hoffman’s melody of Guthrie’s poem

was covered by a gallery of folk and folk-rock musicians over the years, including Joan Baez, Arlo Guthrie, Odetta, the Byrds, and several others. “Deportee” became one of Guthrie’s better known compositions.

After the successful placement of the headstone, Hernandez continued his journey in a new, final direction. With his understanding of the song’s origins and trajectory and his knowledge of the names of the victims and some of their descendants, he plunged into a deeper exploration of the lives of the victims, extracting what he could from stories passed down to surviving relatives and friends about their childhood, education, work, loves, and hopes for the future. In the longest section of the book, entitled “The Stories,” Hernandez offers insights into the lives, personalities, and experiences of Luis Navarro Cuevas, Guadalupe Ramirez Lara, Ramon Paredes Gonzales, and Jose Sanchez Valdivia through interviews with relatives and friends. He also reveals the story of Frank Atkinson, the plane’s pilot, who was born and raised in Rochester, New York, and his wife, Bobbie, who had agreed to serve as stewardess at the last minute in order to replace one who had called in sick. When Guthrie penned his lyrics in 1948, he commented bitterly about the discrimination against agricultural laborers whose only crime was to have been born south of the border: “Both sides of the river I died just the same.” Hernandez shows how the tragedy extended across lines of race, class and ethnicity.

Hernandez’s research and his unusual narrative approach put genuine faces on the souls who died in Los Gatos Canyon. He gives them real names, tells their life stories, and finally allows us to know who they were.

– DARRYL HOLTER

Related:

Listen: Plain Wreck at Los Gatos (Deportee) by Darryl Holter: